Vapor Barrier on cellar dirt floor

fredwe

11 years ago

Featured Answer

Comments (13)

akamainegrower

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoRelated Professionals

Clarksburg Kitchen & Bathroom Designers · East Peoria Kitchen & Bathroom Designers · Gainesville Kitchen & Bathroom Designers · Northbrook Kitchen & Bathroom Designers · Southampton Kitchen & Bathroom Designers · Eagle Mountain Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Feasterville Trevose Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Avondale Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Elk Grove Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Fairland Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Idaho Falls Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Pinellas Park Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Turlock Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Sharonville Kitchen & Bathroom Remodelers · Royal Palm Beach Architects & Building Designersfredwe

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoakamainegrower

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoMaine_Mare

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoakamainegrower

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agofredwe

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoliriodendron

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoliriodendron

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agofredwe

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agobrickeyee

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agorenovator8

11 years agolast modified: 9 years agoakamainegrower

11 years agolast modified: 9 years ago

Related Stories

WINE CELLARS7 Steps to Create a Connoisseur's Wine Cellar

Showcase your wine to its best advantage while ensuring proper storage conditions. Snooty attitude optional

Full Story

KITCHEN DESIGN9 Flooring Types for a Charming Country Kitchen

For hardiness and a homespun country look, consider these kitchen floor choices beyond brand-new wood

Full Story

TILEWhy Bathroom Floors Need to Move

Want to prevent popped-up tiles and unsightly cracks? Get a grip on the principles of expansion and contraction

Full Story

GREEN BUILDINGConsidering Concrete Floors? 3 Green-Minded Questions to Ask

Learn what’s in your concrete and about sustainability to make a healthy choice for your home and the earth

Full Story

SHOWERSYour Guide to Shower Floor Materials

Discover the pros and cons of marble, travertine, porcelain and more

Full Story

BATHROOM DESIGNBathroom Surfaces: Ceramic Tile Pros and Cons

Learn the facts on this popular material for bathroom walls and floors, including costs and maintenance needs, before you commit

Full Story

BATHROOM DESIGNDream Spaces: Spa-Worthy Showers to Refresh the Senses

In these fantasy baths, open designs let in natural light and views, and intriguing materials create drama

Full Story

MORE ROOMS5 Basement Renovations Designed for Fun

Get inspired to take your basement to the next level with ideas from these great multipurpose family spaces

Full Story

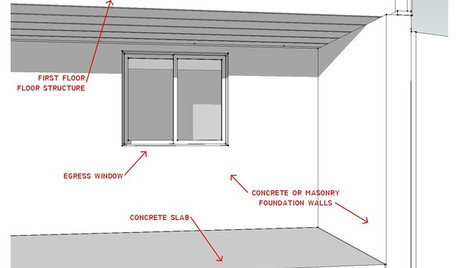

REMODELING GUIDESKnow Your House: The Steps in Finishing a Basement

Learn what it takes to finish a basement before you consider converting it into a playroom, office, guest room or gym

Full StoryMore Discussions

Maine_Mare